The act of revenge as liminal space haunted by the ghosts of rememberings, aching for present-future materiality in Djbril Diop Mambéty’s ‘Hyenas’ (Hyènes, 1992)

Colobane is moribund. A scene of arrested development. Its inhabitants are shadows of themselves. The viewer arrives in this place to experience a little warm death, served coldly. Workless men covered in indigence amble, downbeat, to haunt Draman Drameh’s (Mansour Diouf) store-cum-bar, where they cannot afford a drink. Its municipality is shuttered, as the Town Hall is retired, its contents carried off by creditors. There has been no progression. Time has stood still. The present a fulsome nostalgia. There is no industry, no livelihood and no trade. Trains no longer stop and go there. Colobane is nowhere. “This town, is coming like a ghost town”1, but it is not forgotten so much as it is engaged in informal acts of forgetting, and for which it is unforgiven.

Communality, though, can still be located in this town; it is the resource that has survived the ravages of intemperate economics. ‘Colobane was, despite its poverty, characterized by a spirit of community and cooperation. The men in the pre-opening sequence move together into Draman’s store. The women who come into the store wait patiently together, joking with one another.’2 Draman – a man of the people – supplies the men with drink, though they have no money, and in gratitude they in turn carouse with him. Emeakaroha posits: ‘The philosophy behind the African communalism, therefore guaranteed individual responsibility within the communal ownership and relationship. The prosperity of a single person, says an African adage, does not make the town rich. But the prosperity of the town makes persons rich.’…”Poverty was a foreign concept…It never was considered repugnant to ask one’s neighbours for help if one was struggling…”…This explains why a community may have poor people but it may not have beggars.’3 Song and dance is interrupted by a rousing train track delivering a revenant, who provokes an unofficial act of remembering, impugning this morality as perhaps a song-and-dance itself – a phantasm.

Before the haunting begins possession takes place. Linguère Ramatou’s (Ami Diakhate) divestment impoverishes Colobane and its duppy conjures memories of a betrayal that sets off an unravelling where the one thing left that holds the town together, falls apart – a ghosting. The repossession of the Town Hall and the Mayor (Mamadou Mahourédia Gueye) telling his wife, “…go to hell if you want” are the little earthquakes that portend the bulldozing to come. Linguère is returned after 30 years. She is not as she was then, when she was falsely accused by her then lover Draman; shamed, exiled and left pregnant, outside of her community, to fend for herself in the world – a ghosting. She is old, “…rich as the World Bank…”, and it appears is only partly human – her body crowned by two phantom limbs of gold. Is she living, is she dead or is she both? She occupies the town’s periphery watching patiently as Colobane dissembles at the prospect of receiving her wealth. Her haunting has given rise to what Fela Kuti called i“Unnecessary Begging“4.

In the temporality Linguère has brought with her and placed Colobane in, encomiums and eulogies border each other, as Draman, the Mayor and the other Town Councillors meet at the old ‘Hyena Hole’ and desperately resurrect her as a fabulation of who she was (and what they were) – ‘…stories that emphasise a completely imagined and publicly constructed view of her as selfless and generous and that sentimentally position her as a long-lost daughter who is finally returning to the place she belongs’5. False memory producing yet another ghosting. We can surmise that it was these accomplices who banished Linguère; the accompanying ignominy and isolation making her a ghost of herself, transmuting her body and the values it embodied, forcing it into a life of prostitution. Involuntary dislocation also made a ghost of her baby after just one year, yet she remains remembered and loved in the spectral landscape of revenge.

Revenge is a liminal space where memories remain vivid and each facet of time (past, present and future) exist at once. For Linguère it is a place of agency, isolation (as a choice), materialistic individualism and justice. ‘She returns in order to exact a toll: she wants revenge (not compensation) for the previous injustice done to her and she wants a revision in [C]olobane’s public memory.’6 Conveniently, the sinner is now regarded as the town’s saviour, “…only she can pull Colobane out of its abyss…” She offers 100,000 Million CFA, half of which the townspeople can share amongst themselves, on the condition that she is able to buy the Court and “…if someone will kill Draman Drameh.” “Ancient history”, “…not important…” and “…the case is over now,” are the protestations of Draman to the bounty that has been placed on his head. However, in revenge, past, present and future coalesce, so the ghosting of Linguère and her daughter is simultaneously recent, critical and extant. Asked by Draman, “Who can turn back time?”, she answers, “I can.”

Despite the western trappings and the marked individualism revenge speaks to, as a temporality at least it can be seen to be consistent with Linguère’s heritage; Emeakaroha states, ‘In the African culture, time is polychronous in the sense that a person can do three [past, present, future] or more things within a given period but simultaneously.’7 He also asserts that time within African cultures is socialised, ‘”Thus time apart from being reckoned by such events as the first and second cock-crow, sunrise, sunset, overhead sun, or length of shadow, is also reckoned by meal-times, wine-tapping times, time of return from the farm and so on. These factors are not arbitrary. For instance, the use of meal periods does not imply that all eat their meals at exactly the same time, but that everyone has a reasonably accurate idea of what is meant.”‘8 The spectre of Linguère, the outcast, has long motivated Colobane’s routine of forgetting, delineated by events such as those listed above, but she is long unsocialised – apart from their communality – her exile is a single act repertory and “…she has a phenomenal memory.”

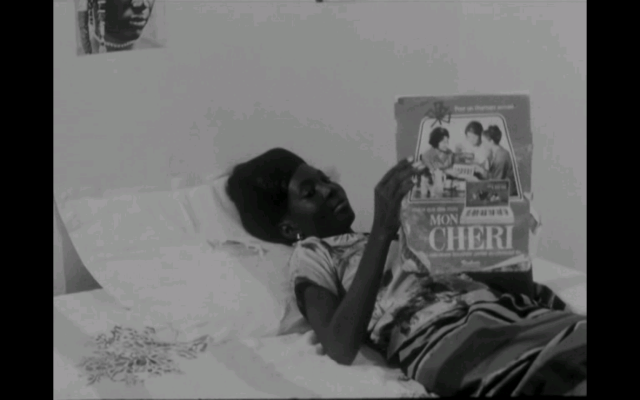

All that glisters is gold in Hyenas, but is of no intrinsic value. Linguère is literally made of gold but she evokes no warm sentiment in the people of Colobane. Her caché is in her riches, and the towns citizens ‘act according to a master narrative in which the lost child returns to the fold and the social order is set right’9, so as to get their hands on them. The indignation at her indecent proposal, where the Mayor waxes, “We are in Africa but the drought will never make us savages…rather starvation than blood on our hands…”, is temporary. The indigents that introduce the film are suddenly shod in ‘golden’ leather shoes from Burkino Faso, the Police Chief has a new gold tooth, the local place of worship is flooded in the crystalline sparkle of its new chandelier, and the town’s women are blinded by a horde of white goods. These things either serve no practical purpose or reify an absence that was never felt in the first instance – high end work boots where there is no work and electric fans where there is no electricity. ‘It becomes apparent that the imported commodities are a mere illusion, not only for their “useless” nature, but the way they are owned, and more importantly, given away at the carnival…’10 The opalescence of Linguère’s things is so desirous that no kind of exorcism (shunning, exile, death) is ever contemplated.

Le Professeur (Issa Ramagelissa Samb) and the town’s Doctor attempt to shatter the illusion, to assure Colobane’s recovery is more than just a promise of wealth, and so visit Linguère. “We need credit, so we can work and our economy can flourish again.” She refuses to underwrite the town’s recovery, telling them that she already owns everything and that is was she that closed the factories and snubbed the potential gold mining and oil drilling. In this moment the reality is clear – this wealth is without currency for Colobane; it is a phantom born of its ghosting of Linguère and “This place, is coming like a ghost town”11, because it haunts her. Yet the two visitants suspend their disbelief and participate in a murderous act of joint enterprise in the final scenes of the film. Colobane, understandably given its dire straits, declares several times in the film, with an element of novelty, that Linguère is as “rich as the World Bank”, but the Senegambian region of West Africa, as part of the Empire of Mali, has a rich legacy of vast wealth. Robin Walker says:

‘In a recent book, Cynthia Crossen, senior editor of the prestigious financial newspaper Wall Street Journal, wrote: “You’ve heard about the extraordinary wealth of Bill Gates, J. P. Morgan, and the sultan of Brunei, but have you heard of Mansa Musa [I], one of the richest men who ever lived? Continuing this theme, Mrs. Crossen comments that: “Neither producer nor inventor, Mansa Musa was an early broker, greasing the wheels of intercultural trade. He created wealth by making it possible for others to buy and sell”. He then refers to Dr. Basil Davidson who suggested the rulers of Mali were, ‘”rumoured to have been the wealthiest m[e]n on the face of the earth.”‘12 ‘Musa I embarked on a large building programme, raising mosques and universities in Timbuktu and Gao.’ …Timbuktu rose from obscurity to great commercial and cultural importance.’13

Perhaps this record of former glories transferred through the iiijeli (griot) tradition, unconsciously fuels Colobane’s expectations of Linguère, but incalculable wealth is the point where she and Mansa Musa diverge. Musa, celebrated for making the Malian Empire (c1230-1670) an epoch of world renown and Linguère who will, “…make the whole world a brothel.”

The egalitarianism that undergirds Colobane’s communality, earlier insinuated to be a ‘song-and-dance’, later proves to be a phantasm that is carnivalesque. ‘After Ramatou’s revelation…the community spirit disappears, even if it is constantly invoked as a justification for killing Draman. Fights and disputes become the norm among the men. The women waiting at the store no longer enter together; they jostle each other for position, talk over one another, and are no longer cordial.’14 If it is communality predicated on a ‘solidarity in adversity’15 that renders everyone equal, it does not however, make them feel that they are the same – the spectre of money disrupts the equilibrium of the ii‘Clan vital’ (the living clan)16. The cordiality of inconvenience cleaves the community together then apart. By the time Draman is offered a rifle to kill himself a second time, by the previously indignant Mayor, the man of the ‘clan’ has himself become a ghost, haunting the town in search of security from townspeople to whom he is already dead. ‘The viewer is gradually primed to witness Draman’s murder as an ultimate expression of the greed of the townspeople disguised within an appeal for revenge.’17 ‘Ramatou [who] is able to buy the ‘soul’ of Colobane with the promise of consumer happiness.’18 What is left after such a transaction is unhuman, another kind of walking dead to join Draman in this ghosting of Colobane.

‘Death [in Africa] is a natural transition from the visible to the invisible or spiritual ontology where the spirit, the essence of a person, is not destroyed but moves to live in the [community of the] spirit ancestors’ [living dead] realm. (King, 2013)’19…as long as the living dead is remembered and continues to influence the actions of the living.’20 Mambéty, with a little sleight-of-hand, subverts this understanding of death: Colobane is the community of the living dead and Linguère’s revenge both interweaves their connection and makes herself remembered in the actions of the town, as it is pushed towards an acknowledgment of her story. In Baloyi’s conception of death, quoted above, one must be part of a community that actively engages in the act of remembering for one’s spirit to ascend. Linguère was forgotten in her death (defamation, exile and shame) and became ghoulish. Draman too, gradually becomes immaterial to the citizens of Colobane, soon to become subject to the ultimate act of consumerism. ‘Draman represents a blockage in multiple senses of the term. Not only does he block access to an otherwise attainable goal but his presence remains a constant reminder of an unfinished or inadequate confrontation with the past. In other words, he reminds the town of its own blockage of memory. His presence threatens a constant return of repressed material.’21 ‘His death is also the death of what made us human in the first place – our morality, which was itself developed to keep tyrannical behavior in check for the survival of the community or band.’22

Revenge is not the only malevolent presence corrupting Colobane. A 2010 report on gender opportunities in Senegal for USAID says, ‘Despite the encouraging legislative and policy environment, women and men in Senegal face very different sets of opportunities in most spheres of life…Cultural beliefs typically support the dominance of men in social life, and women are first and foremost expected to be good wives and mothers. Thus, women do not yet have equal rights with men…especially in rural areas…’23 Hyenas appears to be set in 1975 and was made in 1992; then as now the eidolon of patriarchy remains and is the root cause of Linguère’s very real suffering and pain. She buys the local court because the law permits the cowardly lies of Draman, the alcohol inspired corrobarating fictions of two other men and the town’s all male jury to conspire in determining her fate. ‘Discriminatory legislation persists, notably in family law, as well as harmful traditional practices, such as early and forced marriage and female genital mutilation, widespread violence against women, limited access to education, employment, decision-making positions, health services and land. Moreover, women remain widely under-represented in public and political affairs.’24

The patriarchate haunting is so extreme that it has taken possession of the women in the town. There are none that keen for her. The first two people to jump to Draman’s physical defence in the face of Linguère’s proposal are his wife, Khoudia Lo (Faly Gueye) and another woman. The only woman that wields any influence in Colobane is Khoudia Lo, whose threat is that of a ‘harridan’. Khoudia Lo is clearly much more business savvy than her husband and yet with congeniality his only accomplishment he is feted as the town’s next mayor. Despite Draman’s unavoidable guilt and Linguère first instruction on her return to Colobane being to set up a “Colobane Women’s Fund”, no woman supports her nor chastises him or his accomplices. Linguère must become as rich as the World Bank and own the processes of law, to have agency enough to obtain a sort of justice. In this place, where not a single citizen contemplates an ‘amende honorable’ or personal apology, Linguère’s haunting of Colobane exacts an involuntary atonement by ensuring “This town, is coming like a Ghost Town”25.

Fool’s paradise

Was it very nice?

People living in the world for material things

Love has a playful heart

That’s where the hatred starts

Causin’ harm and replacin’ the joy true love can bring26

I look forward to your musical responses to this mixtape. Click here for a full track listing.

END

Notes

i. Fela says ‘Unnecessary begging’ in area (Ghetto) rules is not done—it is not necessary. In the ghetto, if you give your word, people believe you for such words until you do otherwise. African ghetto thoughts and deeds are the traditional way of life of the people. They are based on age-long belief that: ‘words are like eggs, when they drop, they cannot be taken back—it is not necessary. However today, sings Fela, some of us in the spirit of trust believe in our governments. We go into agreement with them to provide us (the people) good houses, good roads, keep the economy buoyant. What do the people get? No government. Corruption at the highest level, etc.! With all this, there are still some academics who preach patience, ‘Intellectuals’ and ‘leaders of thought’ who try to justify the mismanagement of African lives by those in government as ‘problems of young democracies’. Fela says this is Unnecessary Begging. He calls on those in power, to beware of the day when the people will revolt against this situation. It will be a day to render accounts, there will be no room for any Unnecessary Begging.

[Mabinuori Kayode Idowu, https://felakuti.bandcamp.com/album/unnecessary-begging-1976]

ii. Communalism in Africa is a system that is both suprasensible and material in its terms of reference. Both are found in a society that is believed by the Africans to be originally “god-made” because it transcends the people who live in it now, and it is “Man-made” because it cannot be culturally understood independent of those who live in it now. Therefore, the authentic African is known and identified in, by and through his community… The community is the custodian of the individual hence he must go where the community goes…This community also, within this transcendental term of reference (god-made), becomes the custodian of the individual’s ideas. This is why, beyond the community – the clan – for the African, “there stood the void in strong and ever-present contrast. Outside this ancestrally chartered system there lay no possible life, since ‘a man without lineage is a man without citizenship’: without identity, and therefore without allies…; or as the Kongo put it, a man outside his clan is like a grasshopper which has lost its wings”. The clan here is ‘clan vital’ that is ‘a living clan’.

[http://www.emeka.at/african_cultural_vaules.pdf]

iii. Griot, Mande jeli or jali, Wolof gewel, West African troubadour-historian. The griot profession is hereditary and has long been a part of West African culture. The griots’ role has traditionally been to preserve the genealogies, historical narratives, and oral traditions of their people; praise songs are also part of the griot’s repertoire. Many griots play the kora, a long-necked harp lute with 21 strings. In addition to serving as the primary storytellers of their people, griots have also served as advisers and diplomats. Over the centuries their advisory and diplomatic roles have diminished somewhat, and their entertainment appeal has become more widespread. [https://www.britannica.com/art/griot]

References

1, 11, 25, Ghost Town by The Specials

[7”, Single, Two-Tone Records, CHS TT 17, UK, 1981]

2, 14, Of Cowboys and Elephants: Africa, Globalization and the Nouveau Western in Djbril Diop Mambety’s Hyenas – Dayna L. Oscherwitz

[Research in African Literatures, Vol. 39, No.1 (Winter 2008) p.232, 232]

3, 7, 8, 16, African cultural values – Dr. Emeka Emeakaroha PhD.[http://www.emeka.at/african_cultural_vaules.pdf]

4, Unnecessary Begging – Fela Kuti

[No Bread (LP, Album), Soundworkshop Records, SWS-1003, Nigeria 1975]

5, 6, 9, 21, Dependency, Appetite, and Iconographies of Hunger in Mambéty’s Hyenas – Burlin Barr

[Social Text, Volume 28, Number 2 103: 57-83, 2010, p.67, 67, 68, 76, 77]

10, 17, The Representation of Globalization in Films About Africa – Abdullah H. Mohammed, PhD

[A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University, In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree, Chapter 1: Hyenas: As Violent as the World Bank, p.44-91, August 2012, p.66, 86,

https://etd.ohiolink.edu/rws_etd/document/get/ohiou1340130831/inline]

12, 13, When We Ruled: The Ancient and Mediaeval History of Black Civilisations – Robin Walker

[Reklaw Education Ltd, 2nd Edition, ISBN: 978-0-99310-200-4, 2013, p.442, 444]

15, 18, Postcolonial African Cinema: Ten Directors – David Murphy, Patrick Williams

[Djibril Diop Mambéty, pp.96-109, Manchester University Press, ISBN 9780719072024 (hbk.) ISBN 9780719072031 (pbk.), 2007, p.107, 104, 107]

19, 20, The African Conception of Death: A Cultural Implication – Lesiba Baloyi

[Dr George Mukhari Academic Hospital, Molebogeng Makobe-Rabothata, University of South Africa, South Africa, p.235-236, http://www.iaccp.org/sites/default/files/stellenbosch_pdf/Baloyi.pdf]

22, Neoliberalism and the New Afro-Pessimism: Djibril Diop Mambéty’s Hyènes – Charles Tonderai Mudede

[e-flux, Journal #67 – November 2015, http://www.e-flux.com/journal/67/60719/neoliberalism-and-the-new-afro-pessimism-djibril-diop-mambty-s-hynes/]

23, Gender Assessment, USAID/ Senegal Prepared by: Deborah Rubin, Team Leader, Cultural Practice LLC with assistance from Oumoul Khayri Niang-Mbodj, DevTech Systems, Inc.

[This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by DevTech Systems, Inc., for the Short-Term Technical Assistance & Training Task Order, under Contract No. GEW-I-01-02-00019. June 2010, p.11, http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pdacr976.pdf]

24, “Gender inequalities and development: a picture of Fula women in the border area of South-eastern Senegal through a gender analysis” – Giovanna Basso

[An Individual Study Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master degree in Cooperation and Development, Academic Year 2013/2014, p.9, https://www.ong-aida.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/An%C3%A1lisis-de-g%C3%A9nero-sobre-la-mujer-peul-%E2%80%93-Senegal-2014-EN-.pdf]

26, Fool’s Paradise – Rufus featuring Chaka Khan

[Rufus Featuring Chaka Khan (LP, Album), ABC Records, ABCD-909, US, 1975]

Bibliography

- Neoliberalism and the New Afro-Pessimism: Djibril Diop Mambéty’s Hyènes – Charles Tonderai Mudede

[e-flux, Journal #67 – November 2015, http://www.e-flux.com/journal/67/60719/neoliberalism-and-the-new-afro-pessimism-djibril-diop-mambty-s-hynes/] - THE HYENA’S LAST LAUGH: A conversation with Djibril Diop Mambety – Frank Ukadike,

[Transition 78 (vol.8, no. 2 1999), pp. 136-53. Copyright 1999, W.E.B. Dubois Institute and Indiana University Press. Posted with Permission. View at http://www.jstor.org/stable/2903181., http://newsreel.org/articles/mambety.htm] - Touki bouki: Mambéty and Modernity – Richard Porton

[The Criterion Collection/ CURRENT, 10th December 2013, https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/2988-touki-bouki-mambety-and-modernity] - Dependency, Appetite, and Iconographies of Hunger in Mambéty’s Hyenas – Burlin Barr

[Social Text, Volume 28, Number 2 103: 57-83, 2010] - The final scene of Hyenas. A parenthetical incorporation – Kowdo Eshun, Goldsmiths, University of London

[Re-visiones, Number 6, ISSN: 2173-0040, http://www.re-visiones.net/ojs/index.php/RE-VISIONES/article/view/173/244] - Of Cowboys and Elephants: Africa, Globalization and the Nouveau Western in Djibril Diop Mambety’s Hyenas – Dayna Oscherwitz

[Research in African Literatures, 2008, https://www.academia.edu/11171127/Of_Cowboys_and_Elephants_Africa_Globalization_and_the_Nouveau_Western_in_Djibril_Diop_Mambetys_Hyenas%5D - Reviews: Hyenas – Esi Eshun

[New Internationalist, 5th October 1998, https://newint.org/features/1998/10/05/review] - Postcolonial African Cinema: Ten Directors – David Murphy, Patrick Williams

[Djibril Diop Mambéty, pp.96-109, Manchester University Press, ISBN 9780719072024 (hbk.) ISBN 9780719072031 (pbk.), 2007] - The Representation of Globalization in Films About Africa – Abdullah H. Mohammed, PhD

[A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University, In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree, Chapter 1: Hyenas: As Violent as the World Bank, p.44-91, August 2012 https://etd.ohiolink.edu/rws_etd/document/get/ohiou1340130831/inline] - Mambety’s Hyenas: Between Anti-Colonialism and the Critique of Modernity – Richard Porton

[Iris 18, Spring 1995, pg. 95-103] - Cinematic Wealth vs. Spiritual Poverty: Mambety’s HYENAS – Phillip Maher

[Facebook, October 6, 2010 at 5:34pm, https://www.facebook.com/notes/fandor/cinematic-wealth-vs-spiritual-poverty-mambetys-hyenas/156111951088355/] - African cultural values – Dr. Emeka Emeakaroha PhD.[http://www.emeka.at/african_cultural_vaules.pdf]

- African Concept of Time, a Socio-Cultural Reality in the Process of Change – Sunday Fumilola Babalola and Olusegun Ayodeji Alokan

[Journal of Education and Practice, Vol.4, No.7, 2013, ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online), www.iiste.org, http://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/JEP/article/view/5290%5D - Long Past, limited present and no future: a critical discussion of John Mbiti’s African concept of Time – Hendrik Barnard, St John Vianney Theological Seminary, Student, Undergraduate

[https://www.academia.edu/7289018/African_Concept_of_Time] - Africa Shoots Back: Alternative Perspectives in Sub-Saharan Francophone African Film – Melissa Thackway

[Chapter 4: Memory, History: Other Stories, p.93-119, Publisher: Boydell & Brewer (1 Dec. 2003), ISBN-10: 0852555768, ISBN-13: 978-0852555767] - Speaking with revenants: Haunting and the ethnographic enterprise – Katie Kilroy-Marac, University of Toronto Scarborough, Canada

[Ethnography, 2014, Vol. 15(2) 255–276, ©The Author(s) 2013, DOI: 10.1177/1466138113505028, eth.sagepub.com, http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1466138113505028] - African Modes of Self-Writing – Achille Mbembe (translated by Steven Rendall)

[Public Culture 14(1): 239–273, Copyright © 2002 by Duke University Press, http://ghostprof.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Mbembe-African-Modes-of-Self-Writing.pdf] - The African Conception of Death: A Cultural Implication – Lesiba Baloyi

[Dr George Mukhari Academic Hospital, Molebogeng Makobe-Rabothata, University of South Africa, South Africa, p.232-243, http://www.iaccp.org/sites/default/files/stellenbosch_pdf/Baloyi.pdf] - When We Ruled: The Ancient and Mediaeval History of Black Civilisations – Robin Walker

[Reklaw Education Ltd, 2nd Edition, ISBN: 978-0-99310-200-4, 2013] - “Gender inequalities and development: a picture of Fula women in the border area of South-eastern Senegal through a gender analysis” – Giovanna Basso

[An Individual Study Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master degree in Cooperation and Development, Academic Year 2013/2014, https://www.ong-aida.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/An%C3%A1lisis-de-g%C3%A9nero-sobre-la-mujer-peul-%E2%80%93-Senegal-2014-EN-.pdf] - Women in Senegal: Breaking the chains of silence and inequality – UN Working Group on the issue of discrimination against women in law and in practice

[United Nations Human Rights, Office of the High Commissioner, 17th April 2015, http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=15857&LangID=E] - Gender Assessment, USAID/ Senegal Prepared by: Deborah Rubin, Team Leader, Cultural Practice LLC with assistance from Oumoul Khayri Niang-Mbodj, DevTech Systems, Inc.

[This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by DevTech Systems, Inc., for the Short-Term Technical Assistance & Training Task Order, under Contract No. GEW-I-01-02-00019. June 2010, http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pdacr976.pdf] - Fool’s Paradise – Rufus featuring Chaka Khan

[Rufus Featuring Chaka Khan (LP, Album), ABC Records, ABCD-909, US, 1975]